Risks of retreat: The enduring inclusion imperative

18 min read

| Published on

Executive summary

The field of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) is facing significant legal and social threats, prompting some organizations to retreat from efforts aimed at advancing fairness in the workplace. New data from a survey of 2,500 US employees conducted by Catalyst and the Meltzer Center for Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging in 2025 reveal significant risks of such a retreat in four areas:

- Talent risks: Employees strongly support DEI programs and consider an employer’s commitment to DEI when making career decisions.

- Financial risks: Respondents are more likely to purchase products or services from organizations that support DEI.

- Legal risks: C-suite and legal leaders recognize that a retreat from DEI could lead to a workplace that is less fair, increasing the risk of discrimination claims by members of marginalized groups.

- Reputational risks: While many leaders believe their organization’s commitment to DEI remains strong, employees tend to be more skeptical, revealing a disconnect between how leaders think they are acting and how employees interpret those actions.

Given the significant legal and social risks of maintaining DEI work and the significant legal and social risks of retreating from DEI work, this report offers four practical recommendations for how leaders can assess risk in DEI programs, modify programs as necessary, align communications to their strategy, and maintain commitment even in the face of headwinds.

How to cite: Pollack, A., Glasgow, D., Van Bommel, T., Joseph, C., & Yoshino, K. (2025). Risks of retreat: The enduring inclusion imperative. Catalyst & Meltzer Center for Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging.

Introduction

Any organization seeking to thrive in the twenty-first century must promote fairness and equal opportunity.1 In the recent past, much of this work has fallen under the umbrella of DEI.2 But now, at least in the United States, many business leaders are caught in the middle of competing pressures.

On one side, the field of DEI is facing significant legal and social threats, including lawsuits from anti-DEI advocacy groups, social media campaigns, and orders and investigations by US federal and state government actors.

On the other side, many leaders remain committed to the values of diversity, equity, and inclusion for moral, business, and legal reasons, and understand that employees and consumers often expect them to defend and protect the work. In addition, leaders of global organizations are aware that many countries are doubling down on DEI policies.

In balancing these dueling pressures, leaders need to know:

- How to navigate the current risk landscape for DEI work in the United States.

- How to benchmark their DEI strategy against that of organizational peers.

This research report — leveraging data collected against the backdrop of the current landscape, from January 20 to February 11, 2025 — offers critical and timely insights on both these subjects.

The backdrop

While the term “DEI” is relatively new, the work of promoting equal opportunity in employment has existed since soon after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.3 Organizations generally adopt diversity initiatives to promote fairness (the “moral case”), enhance organizational performance (the “business case”), and mitigate the risk of discrimination claims (the “legal case”).4

Yet in recent years, DEI programs have come under attack, causing significant new risks to emerge. The US Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard prompted a surge in lawsuits challenging private-sector diversity, equity, and inclusion practices in the workplace under two principal laws:5

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (“Title VII”), which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, and sex (including sexual orientation and gender identity).6

- 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (“Section 1981"), which prohibits race discrimination in contracting.7

Aside from the legal challenges, organizations have also faced social and reputational risks associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion. Activists have attacked companies with DEI initiatives in articles and on social media, causing some to retreat.8 Public companies have also faced an increase in shareholder proposals seeking to pressure companies to abandon their diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.9 In fact, around six out of 10 C-suite and legal leaders in our survey say their organization has experienced pressure to move away from its commitment to DEI, whether from employees, customers or clients, investors, board members, activists, in-house legal or risk teams, and/or partners, such as their supply chain.

Until January 2025, these anti-DEI legal and social pressures mainly emerged from private actors and state governments. However, in recent months, the new federal administration has added to the risks of DEI with actions such as:

- Issuing anti-DEI executive orders, most notably an order on “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity,” which threatens enforcement action against organizations engaged in DEI-related “illegal discrimination or preferences,” and requires federal contractors and grant recipients to certify that they do not operate DEI programs that “violate any applicable Federal anti-discrimination laws.”10

- Appointing opponents of DEI to key agencies such as the Department of Justice and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.11

- Signaling investigations of companies and firms engaged in “unlawful” DEI.12

- Releasing guidance on “unlawful DEI-related discrimination.”13

These actions have caused many organizations — especially federal contractors or grantees — to be concerned about the risk of federal investigations or lawsuits against their DEI initiatives.

The response

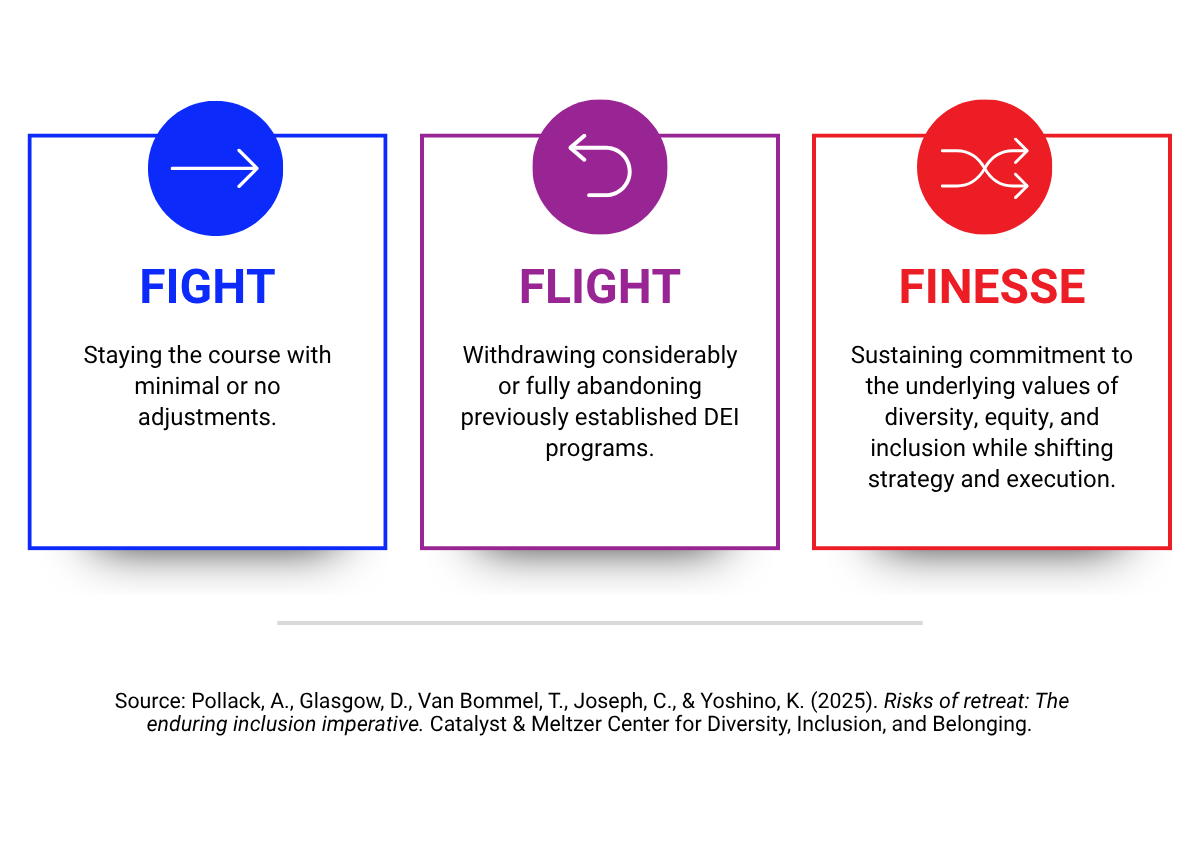

Organizations tend to adopt one of three possible responses to the current landscape — what Catalyst calls fight, flight, or finesse:14

- Fight: Staying the course with minimal or no adjustments.

- Flight: Withdrawing considerably or fully abandoning previously established DEI programs.

- Finesse: Sustaining commitment to the underlying values of diversity, equity, and inclusion while shifting strategy and execution.

For the purposes of this report, we are defining retreat as any adjustment that — intentional or not — is experienced by employees and/or the public as a meaningful move away from established diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and espoused values.

Our data — as well as our ongoing dialogue with leading corporations — suggest that most organizations are adopting the finesse approach. In our survey, the vast majority of executives — 78% of the C-suite15 and 83% of legal leaders16 — say they are “rebranding” their DEI programs with terms such as employee engagement, workplace culture, fairness, or belonging. In tandem with these communication strategy shifts, 21% of C-suite leaders and 23% of legal leaders say they are assessing their investments in DEI programs because of the current environment, while 18% of C-suite leaders and 17% of legal leaders say their company has already reduced its investments.17

As organizations implement such changes, they may face considerable challenges. These include not only the above anti-DEI risks, but also the risks of retreat.

The risks of retreat

Talent

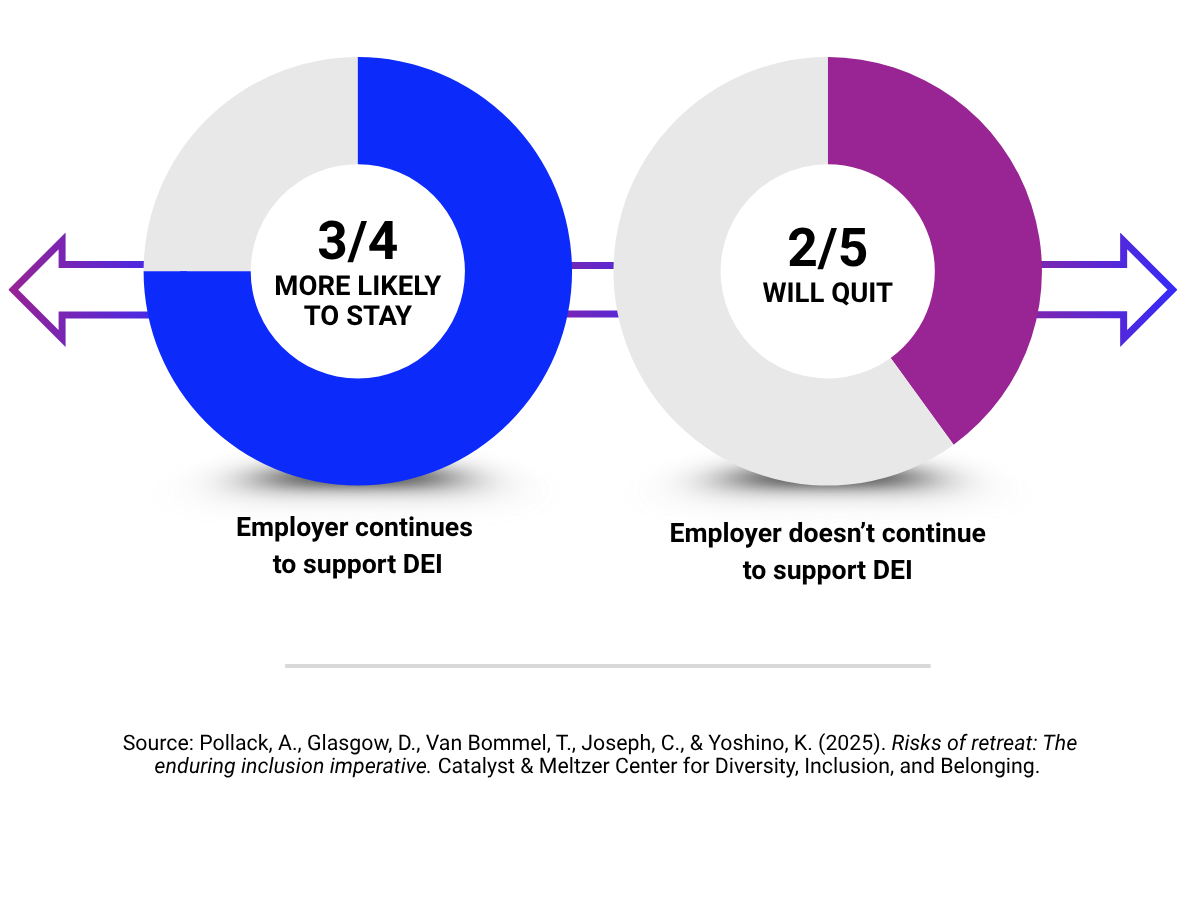

Organizations face the threat of a talent drain if they pull back from diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. More than three out of four employees (76%) say they are more likely to stay with their employer long term if their employer continues to support diversity, equity, and inclusion. Conversely, more than two out of every five employees (43%) say they will quit if their employer doesn’t continue to support DEI, with rates even higher among specific subgroups, including women,18 Gen Z, and millennial employees.19

While many factors, including the macroeconomic environment, make a mass exodus of employees unlikely, this finding suggests a more immediate risk of “quiet quitting” — employees disengaging without formally leaving their jobs — which results in costly loss of productivity and innovation.20

Regardless of whether their employees resign or disengage, organizations risk alienating a majority of their workers if they withdraw from fairness initiatives. A White Baby Boomer man shared, “Such programs promote a positive work environment and make organizations more appealing.” A Latina Gen Z woman highlighted, “DEI programs make me feel safe and empowered.” Both statements point to the void organizations risk creating by retreating. Indeed, one recent study found that among organizations that have rolled back their diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts between January and May 2025, nearly two in five (37%) reported a decline in employee morale, and one in three (33%) cited increased internal conflict or division and difficulties attracting diverse talent.21

Beyond individual accounts, our survey reveals extraordinarily high and, in some cases, nearly universal support for the underlying values of diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example:

- 99% of respondents across job levels agree with the statement: “All workers should feel respected and welcomed at work, regardless of their background or identity.”

- 99% of respondents across job levels agree with the statement: “It’s important that my organization supports fair treatment for its workers, including equitable pay.”

In addition, between 79-93% of employees support 11 programs22 and approaches often implemented to increase diversity of talent, foster inclusive cultures, and build fair systems and structures:

- 93%: Employee resource groups (ERGs).

- 92%: Creating a more inclusive work environment (e.g., nursing rooms, childcare facilities, accessibility for disabled workers).

- 90%: Programs intended to increase representation (e.g., internships, mentorship programs, leadership training).

- 88%: Training on topics like bias, allyship, and inclusion.

- 86%: Workforce diversity hiring goals.

- 86%: Intentional college outreach to diversify job candidate pools (e.g., to historically black colleges and universities or women’s colleges).

- 84%: Involvement with external organizations that support DEI.

- 84%: Supplier diversity policies intended to diversify vendors.

- 84%: Recruitment efforts that focus on marginalized groups.

- 83%: Celebrations of identity (e.g., Pride Month, Black History Month).

- 79%: Compensation incentives or rewards for achieving DEI goals.

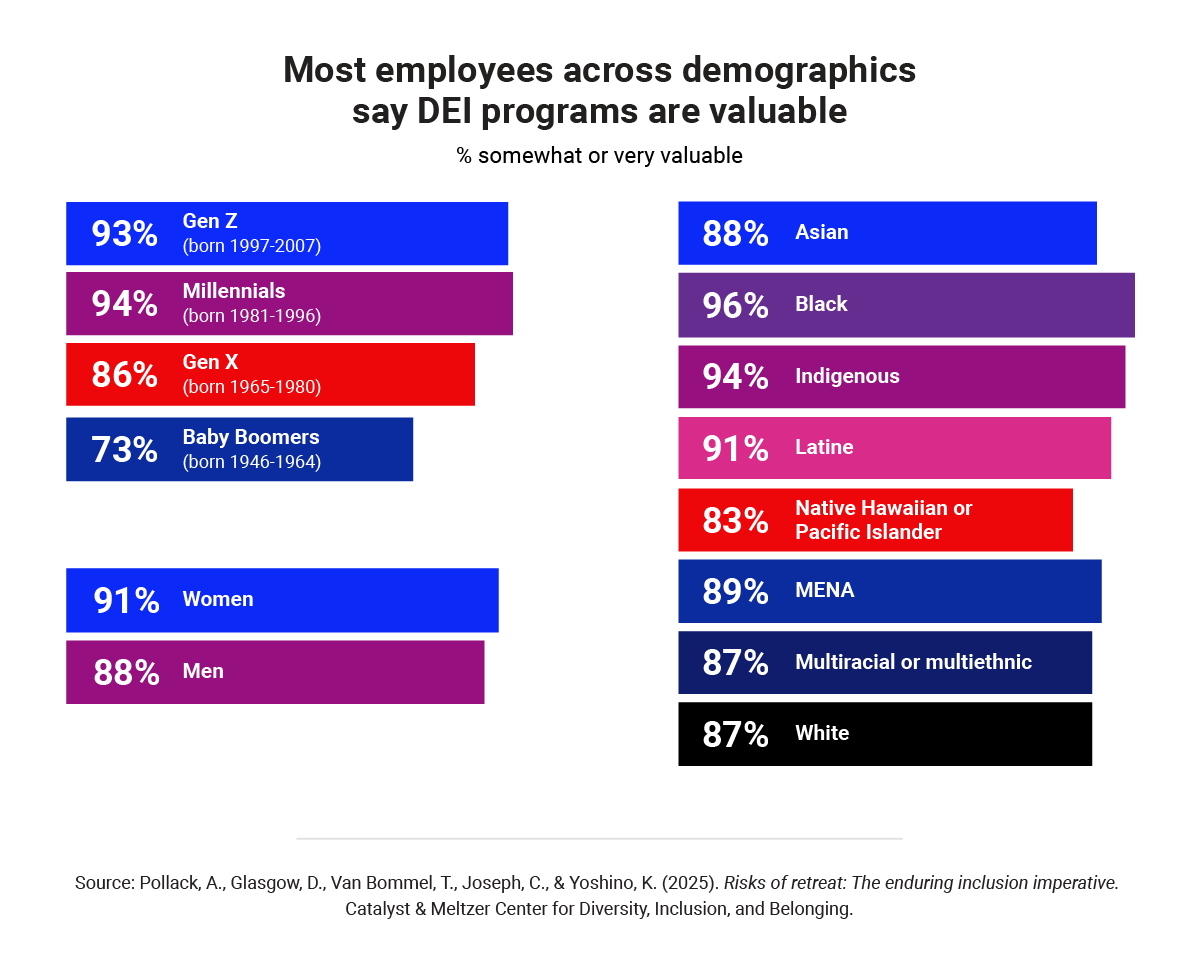

Indeed, across demographic groups, the vast majority of employees find value in DEI programs generally.23

C-suite and legal leaders also see clear benefits to diversity, equity, and inclusion work:

- 84% of C-suite leaders and 83% of legal leaders say that their organization has seen a positive correlation between its DEI programs and employee attraction and retention.

- 83% of C-suite and 86% of legal leaders predict that over the next few years, continuing to support DEI programs will have a positive correlation with employee attraction and retention.

We recognize that the levels of support for diversity programs in our survey are higher than in some other public polling.24 A major difference between our survey and these other polls is that our survey was limited only to employees at medium and large organizations with established DEI programs, while other polls gather data from the general public. This could suggest that the people with the greatest exposure to DEI programs are more likely to support such initiatives than people whose attitudes to DEI are shaped by media narratives or other general perceptions. Given that this study was conducted in the weeks following executive orders targeting DEI, it is also possible that employees and leaders with more favorable views of diversity, equity, and inclusion were motivated to take this survey as a means of responding to the mounting resistance. Ultimately, the reason — or likely the combination of factors — contributing to the uniqueness25 of the results of this data are unknown to us. It is nevertheless a powerful counterpoint to some prevailing narratives that business leaders would be remiss to ignore.

Even in our survey, however, support for DEI programs is not unqualified and many employees recognize room for improvement. Up to half (46-52%) of employees support diversity efforts with no adjustments needed. But about one in three (32-42%) express support for DEI with “adjustments recommended.” ERGs, for example, had the highest overall support among employees (93%) but also one of the highest percentages of employees who were in favor of adjustments (40%).

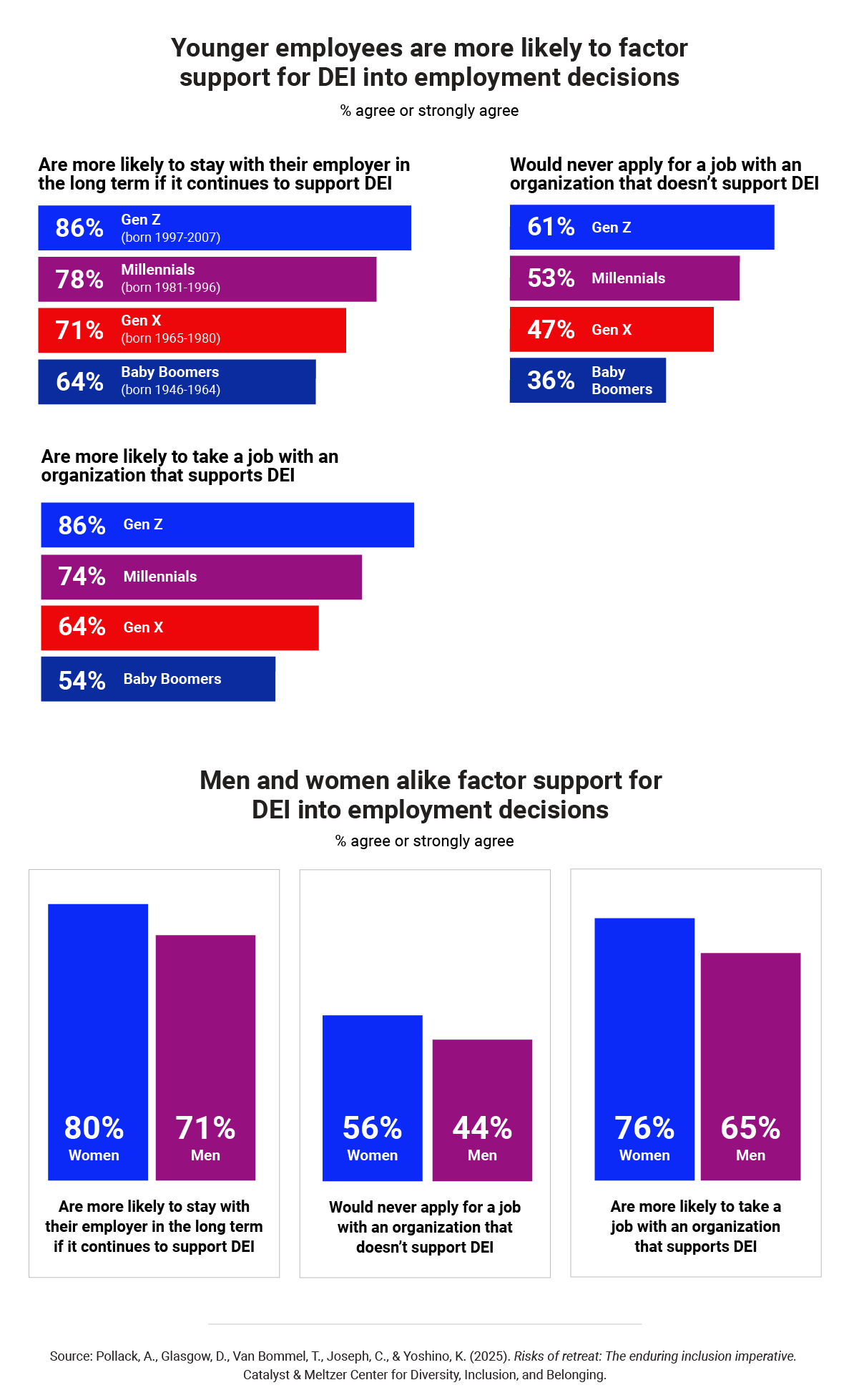

Risks to talent by generation and gender

Digging into specific demographic groups pinpoints where the risks of retreat are greatest.

Generation

Younger generations are more likely to factor an employer’s support for diversity, equity, and inclusion programs into their employment decisions.26

Gender

Men and women alike report that organizational support for diversity, equity, and inclusion influences their employment decisions, with women reporting that it impacts their intent to stay27 and likelihood of pursuing28 or accepting a role29 at higher rates than men.

Financial

Retreating from diversity, equity, and inclusion also carries financial risks driven by external and internal factors. As one Gen X Asian man put it, “Not having DEI initiatives has the effect of leaving money on the table.”

Externally, consumers are increasingly aligning their purchasing power with their values. In recent months, some organizations have seen this play out through loss of customers or partners and boycotts.30 In our survey, 69% of respondents said they would be more likely to purchase a product or service from an organization that supports diversity, equity, and inclusion. In addition, 36% of respondents plan to boycott organizations that are downsizing or eliminating diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

These numbers are even higher among specific subgroups with tremendous economic power. Women, for example, control an estimated $31.8 trillion of worldwide spending.31 And despite not having reached their full economic potential, Gen Z already wields $360 billion in spending power in the United States alone.32 Globally, Gen Z accounts for $9.8 trillion in annual spend, and by 2030, that number will grow to $12.6 trillion (nearly 19% of total global spend).33 Our data show that 74% of women34 and 78% of Gen Z35 in the United States say they would make purchasing decisions based on company DEI policies.

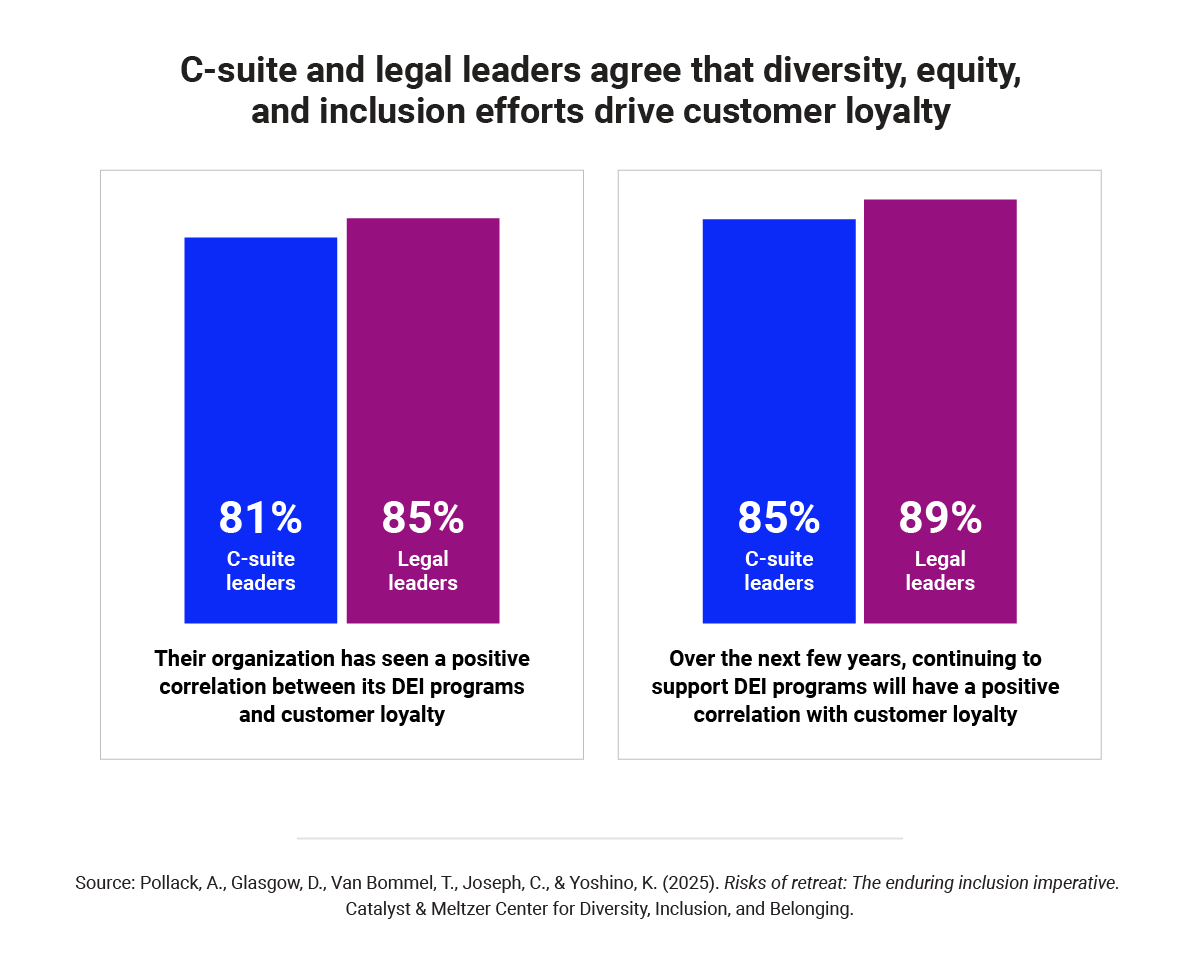

Organizational leaders are clear-eyed about these external financial benefits: more than 80% agree that DEI efforts have a positive effect on customer loyalty.36

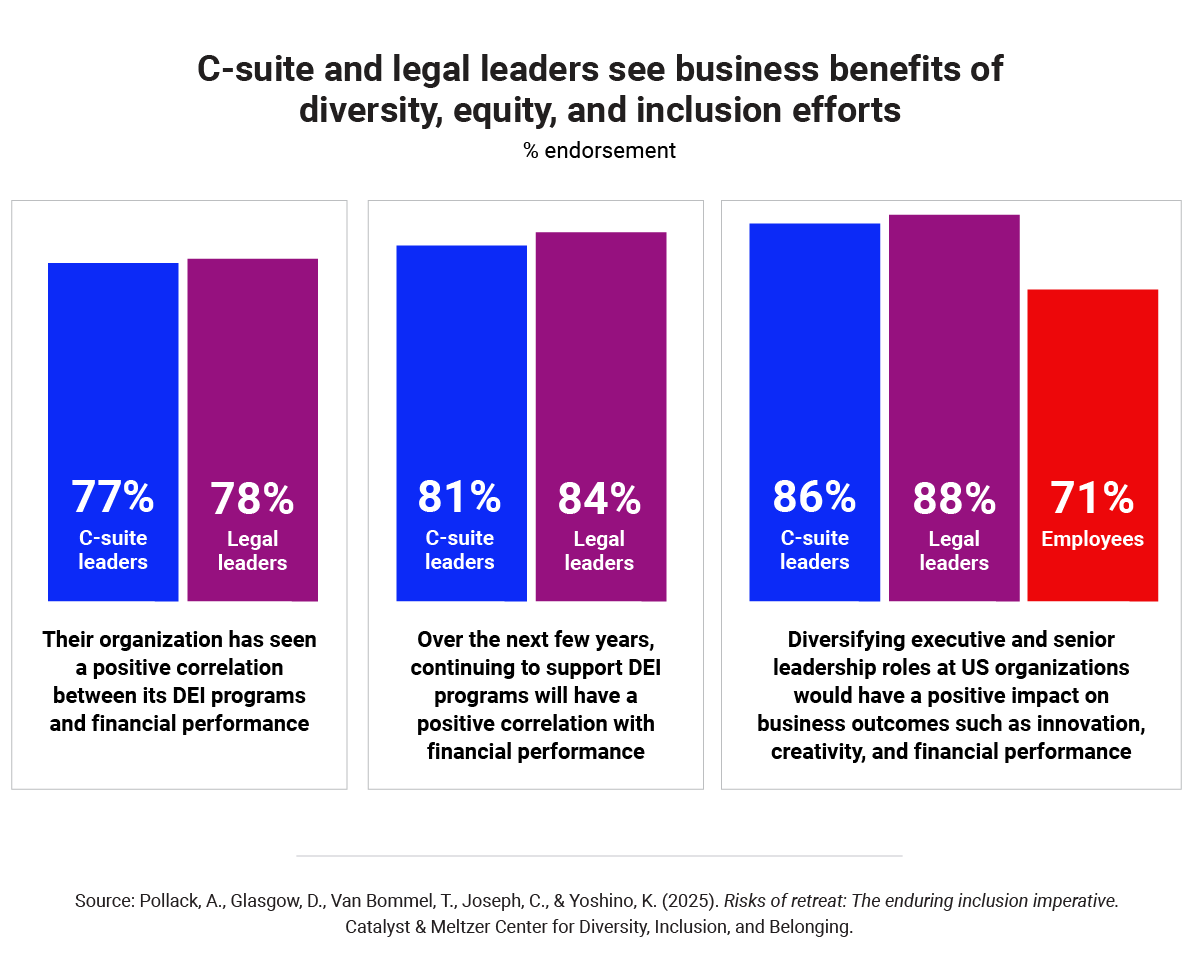

Looking internally, a large majority of C-suite and legal leaders agree that programs related to diversity, equity, and inclusion have driven financial performance in the past37 and will continue to do so.38 C-suite leaders, legal leaders, and employees agree that diversifying executive and senior leadership roles would have a positive impact on business outcomes such as innovation, creativity, and financial performance.39

Employees also experience these efforts as “help[ing] promote people that would have been missed within the company,” as a Black Gen X man pointed out. A White Latina Baby Boomer woman highlighted, “Diversity strengthens teams because everyone can contribute fresh ideas and different perspectives.” An incautious retreat from diversity, equity, and inclusion could deprive organizations of these benefits.

Legal

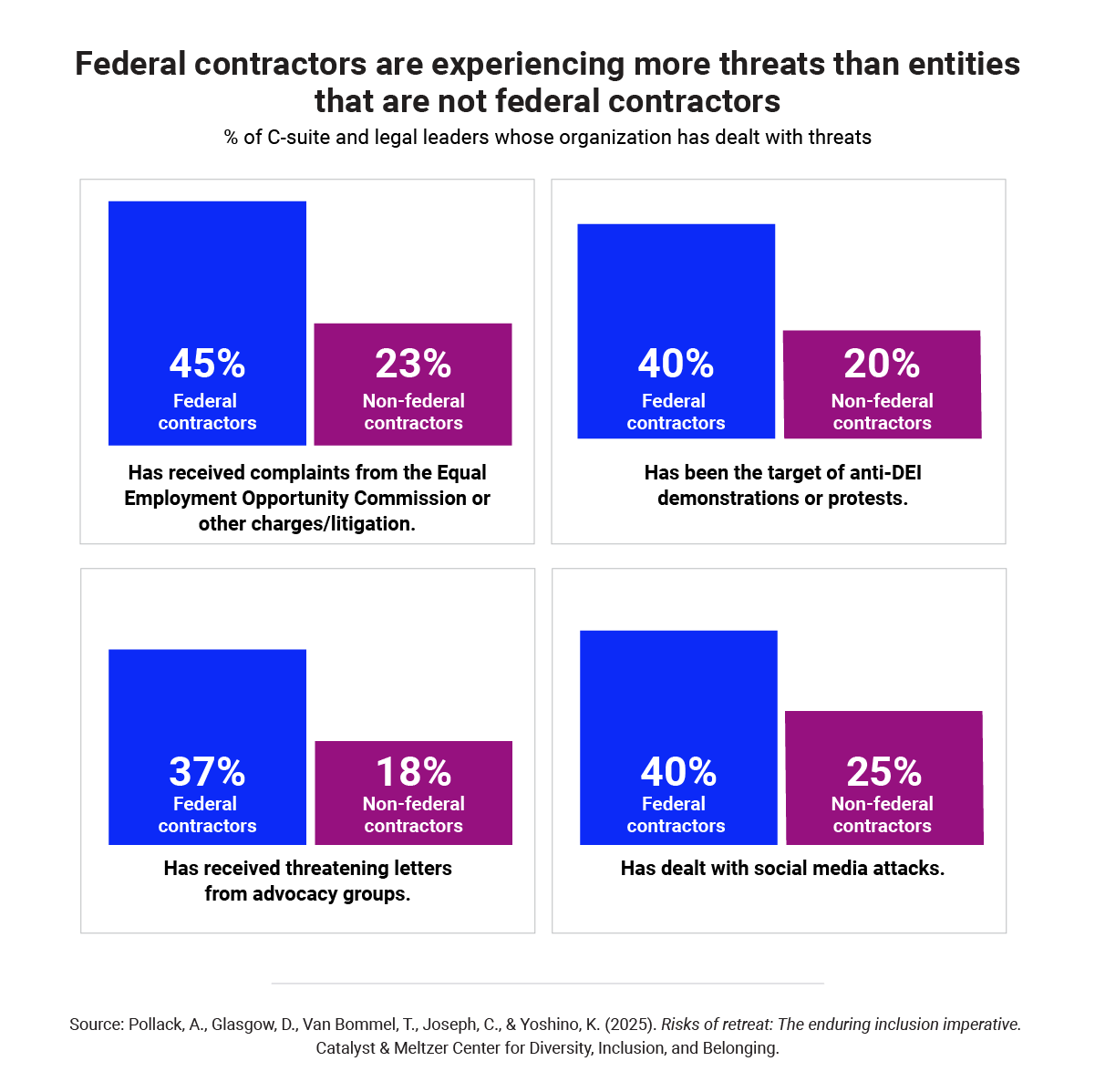

The legal risks of engaging in diversity, equity, and inclusion work are top of mind for many leaders in the current environment. Overall, 55% of the C-suite and 56% of legal leaders say that within the past year, their organization has dealt with social media attacks, threatening letters from advocacy groups, complaints from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or other charges/litigation, or demonstrations or protests against DEI.

Given these real and serious threats, it’s not surprising that our leaders seem well aware of what their organizations are up against and the need to be prepared:

- 93% of the C-suite and 94% of legal leaders say they are either “very” or “somewhat” knowledgeable about the legal compliance of their organization’s DEI programs.

- 62% of the C-suite and 62% of legal leaders say their organization is “completely” prepared to evaluate legal risk and prepare for potential litigation on this topic.

In addition, 86% of the C-suite and 90% of legal leaders say their organization has already taken at least one step to address the potential legal risks of their DEI programs or will do so in the near future.40

At the same time, our data show that organizational leaders are more concerned about the increased legal risk of retreating from diversity, equity, and inclusion:

- 68% of the C-suite and 65% of legal leaders say moving away from DEI would create more legal risk for their organization.

- Specifically, 64% of the C-suite and 62% of legal leaders agree there is greater risk of litigation alleging discrimination from traditional plaintiffs (e.g., people from marginalized racial and ethnic groups, women, LGBTQ+ people, and people with disabilities) than non-traditional plaintiffs (i.e., members of dominant or majority groups).

- 83% of the C-suite and 88% of legal leaders believe organizations should retain or expand their diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, because reducing or eliminating them will create other types of legal risk, such as the risk of litigation from traditional plaintiffs.

The federal contractor experience

Federal contractors are in a more precarious position given their reliance on government funding. For example, they are around twice as likely as entities that are not federal contractors to be dealing with legal and social threats, highlighting a stark contrast.41

In addition, while entities that are not federal contractors are just as likely to have taken one action to address legal risks as their federal contractor counterparts, federal contractors are more likely to have taken two (26% vs 13%) or three actions (9% vs 3%).42

Federal contractors are also concerned about swinging too far away from DEI, but to a lesser degree than entities that are not federal contractors.

- 58% of federal contractors say there is greater risk if they move away from DEI compared to 69% of entities that are not federal contractors.

- 42% of federal contractors say there is greater risk if they continue to support DEI, compared to 31% of entities that are not federal contractors.

Collectively, these findings suggest that leaders understand legal risk in this area as a balancing act. Given that federal law prohibits discrimination based on race, sex, and other characteristics regardless of whether the target belongs to a dominant or non-dominant group, leaders must not inadvertently discriminate against dominant-group members in their DEI programs. On the other hand, leaders recognize that in the absence of DEI programs, members of marginalized social groups are likely to experience more incidents of bias and exclusion. Removing DEI programs therefore increases the risk of discrimination claims by such individuals. As a White Millennial woman noted, “DEI programs confront an issue before it has a chance to fester or turn ugly.”

Our survey suggests that leaders are weighing the legal risk from traditional plaintiffs more heavily than the legal risk from “reverse” discrimination plaintiffs. Despite the intense media attention on the risk of “reverse” discrimination claims, leaders recognize that traditional discrimination lawsuits have not disappeared and that DEI programs are an important way to mitigate the risk of such claims.

Reputational

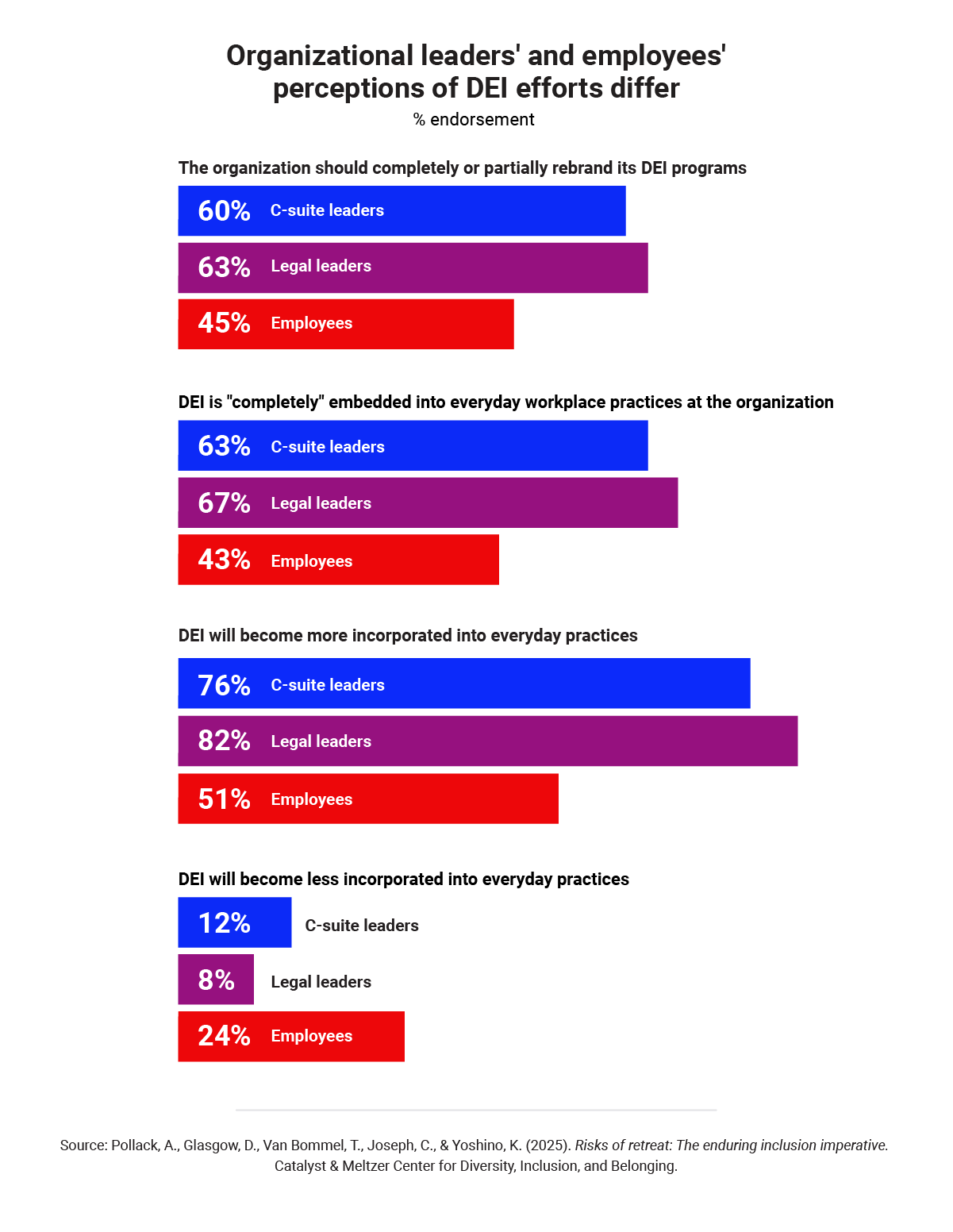

In an environment where it is easy for employees and customers to call out organizations on social media, leaders must be alert to the reputational damage their words, actions, and inactions can cause. Our survey shows that leaders do not believe they are retreating from DEI. However, it also shows, in a manner that should concern those leaders, that employees are less likely to perceive it that way.

For example, leaders indicate that while they are “rebranding” diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, the substance of and commitment to the work remains firm:

- 78% of C-suite leaders and 83% of legal leaders say they are rebranding diversity, equity, and inclusion programs with terms such as employee engagement, workplace culture, fairness, or belonging.

- 62% of C-suite leaders and 60% of legal leaders say their company is either increasing or not changing its investment in diversity, equity, and inclusion.

These results suggest many C-suite and legal leaders are confident and optimistic about their organization’s approach and commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. In fact, about two in three leaders believe diversity, equity, and inclusion are “completely” embedded into everyday workplace practices in their organization. Only 7% of C-suite and 3% of legal leaders anticipate a “significantly reduced or eliminated commitment to DEI” in the United States, with more than 50% saying commitment will increase in the next five years.

Employees, however, are more skeptical. They are less likely than organizational leaders to see a need for rebranding at all.43 They are also less likely to perceive that DEI efforts are already embedded into the workplace,44 and are more likely to expect that DEI will become less embedded at their company in the future.45

These findings suggest that employees are not only experiencing rebranding as retreat, but are also anticipating future retreat. This should be troubling to C-suite leaders, who rank employees as the biggest influencers of their DEI decision-making. A retreat — whether real or perceived — erodes trust in leadership and substantially threatens the reputational advantages that diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives confer to companies.

What’s the path forward?

Read part two of this report to explore four solutions that can help you navigate this complex landscape.

Endnotes

- Why diversity and inclusion matter. (2020). Catalyst.

- Because the survey instrument repeatedly used the terminology of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” and the acronym “DEI,” this report will also regularly use that language. However, we recognize that the terminology in this area is in a state of flux and that many organizations have shifted to other language such as belonging, opportunity, culture, engagement, or inclusion.

- Dobbin, F. (2009). Inventing equal opportunity. Princeton University Press.

- Bowman Williams, J. (2017). Breaking down bias: Legal mandates vs. corporate interests. Washington Law Review, 92, 1473-1514; Georgeac, O. A. M. & Rattan, A. (2023). The business case for diversity backfires: Detrimental effects of organizations’ instrumental diversity rhetoric for underrepresented group members’ sense of belonging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(1), 69–108.

- Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 143 S. Ct. 2141 (2023). In that case, the US Supreme Court found that the race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina constituted unlawful race discrimination. While the Court’s decision was limited to higher education, many lawsuits have asked courts to apply similar reasoning with respect to workplace DEI practices. See the Meltzer Center’s litigation tracker for more information on DEI-related lawsuits.

- Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a). While Title VII does not expressly prohibit sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination, the US Supreme Court in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) held that the statute’s prohibition on “sex” discrimination encompasses a prohibition on sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination.

- 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

- Maclellan, L. (2025, February 1). Major players in the anti-DEI movement: Here’s who’s attacking Goldman Sachs, Pfizer, IBM, and other Fortune 500 companies. Fortune; Ufberg, M. (2024, October 23 ). Robby Starbuck’s anti-DEI activism uses a very familiar playbook. Fast Company.

- Tonello, M. (2025, April 25). The evolving landscape of DEI shareholder proposals. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance.

- Exec. Order No. 14,173. Ending illegal discrimination and restoring merit-based opportunity. (21 January 2025).

- President appoints Andrea R. Lucas EEOC Acting Chair. (2025, January 21). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; Attorney General Pam Bondi dismisses DEI lawsuits involving police officers and firefighters, advances President Trump’s mandate to end illegal DEI policies. (2025, February 26). U.S. Department of Justice.

- EEOC Acting Chair Andrea Lucas sends letters to 20 law firms requesting information about DEI-related employment practices. (2025, March 17). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

- EEOC and Justice Department warn against unlawful DEI-related discrimination. (19 March 2025). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

- CEO action framework. (2025). Catalyst.

- In this study, “C-suite” comprises 800 respondents in an executive leadership role (e.g., CEO, COO, CMO) and 200 respondents in a vice president or director role.

- In this study, “legal leader” comprises 250 respondents employed within an organization's in-house legal department who occupies a leadership role including, for example: General Counsel, Chief Legal Officer, Chief Compliance Officer, Chief Risk Officer, Deputy General Counsel.

- Leaders were asked, “Overall, how is your organization changing its investment in DEI programs (i.e., resource allocation which includes time, people, and money) due to the current environment?” Response options included: We are not changing our investment; we are assessing our investment, but not yet making any changes; we are slightly reducing our investment; we are significantly reducing our investment; we are eliminating our investment (i.e., no longer supporting DEI programs); we are slightly increasing our investment; and we are significantly increasing our investment.

- On a 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) Likert scale, employees were asked how much they agree with the statement, “I’m more likely to stay with my employer in the long-term if they continue to support DEI.” A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of gender on whether employees are more likely to stay with their company long term if their employer continues to support diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F(1, 1235) = 25.90, p < .001. Women (M = 1.86) are more likely to agree that they will stay with their employer long term if they continue to support DEI, compared to men (M = 2.13). On a 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) Likert scale, employees were asked how much they agree with the statement, “If my employer doesn’t continue to support DEI, I’ll leave my job for another employer.” A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of gender on whether employees are likely to quit their job if their employer stops supporting DEI. The results indicated a significant effect, F(1, 1235) = 7.20, p < .01. Women (M = 2.56) are more likely to agree that they will quit their job if their employer stops supporting DEI, compared to men (M = 2.71).

- A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of generation on whether employees are more likely to stay with their company long term if their employer continues to support diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F(3, 1246) = 19.45, p < .001. Bonferroni post hoc tests show that all generations significantly differ from one another (all ps < .05), except for Gen X and Baby Boomers, who do not differ from one another (p = .12). Gen Z (M = 1.71) are most likely to agree, followed by Millennials (M = 1.91), Gen X (M = 2.12), and Baby Boomers (M = 2.31). A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of generation on whether employees are likely to quit their job if their employer stops supporting DEI. The results indicated a significant effect, F(3, 1246) = 64.97, p < .001. Bonferroni post hoc tests show that all generations significantly differ from one another (all ps < .001). Gen Z are most likely to agree (M = 2.14), followed by Millennials (M = 2.48), Gen X (M = 2.86), and Baby Boomers (M = 3.21).

- Allas, T. & Mugayar-Baldocchi, M. (2024, February 28). The hidden costs of quiet quitting quantified. McKinsey.

- 1 in 3 companies that rolled back DEI initiatives are reinstating them. (2025). Resume Templates.

- Of course, not all of these programs are necessarily safe from a legal perspective. Please see the “Assess risk from all angles” section later in this report for a discussion of how to assess legal risk.

- Responses to “In general, how valuable do you feel Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs are?” were dichotomized such that not at all valuable and a little valuable were coded as “0” and very valuable and somewhat valuable were coded as “1.”

- For example, Toplines: April 2025 Times/Siena poll of registered voters nationwide. (2025, April 25). The New York Times; Trump’s job rating drops, key policies draw majority disapproval as he nears 100 days. (2025, April 23). Pew Research Center; Bowman, B. (2025, March 18). Poll: American voters are deeply divided on DEI programs and political correctness. NBC News; Lange, J. & Oliphant, J. (2025, January 28). Americans sour on some of Trump’s early moves, Reuters/Ipsos poll finds. Reuters; Langer, G. (2025, April 26). Trump has lowest 100-day approval rating in 80 years: Poll. ABC News; Peck, E. (2025, January 17). Americans are fine with corporate DEI. Axios.

- A study of 750 business leaders conducted between April 25 and May 5, 2025, by Resume Templates reveals similar findings to our research, suggesting that corporate leader and employee perceptions may indeed be distinct relative to that of the general population.

- Responses to “I’m more likely to stay with my employer in the long-term if they continue to support DEI” were dichotomized such that agree and strongly agree were coded as “1” and disagree and strongly disagree were coded as “0.”A chi square between the dichotomized variable and generation showed a significant association, χ² (3, n = 1,250) = 35.52, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that Gen Z (1.9) and Baby Boomers (-1.9) differed significantly from what was expected. On a 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) Likert scale, employees were asked how much they agree with the statement, “I would be more likely to take a job with an organization that supports DEI.” A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of generation on whether employees are likely to take a job with a company that supports diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F (3, 1246) = 32.05, p < .001. Bonferroni post hoc tests show that all generations significantly differ from one another (all ps < .01): Gen Z are most likely to agree (M = 1.71), followed by Millennials (M = 2.01), Gen X (M = 2.25), and Baby Boomers (M = 2.53). Responses to “I’m more likely to take a job at an organization that supports DEI” were dichotomized such that agree and strongly agree were coded as “1” and disagree and strongly disagree were coded as “0.” A chi square between the dichotomized variable and generation showed a significant association, χ² (3, n = 1,250) = 68.13, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that Gen Z (3.0) and Baby Boomers (-2.8) differed significantly from what was expected. On a 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) Likert scale, employees were asked how much they agreed with the statement: “I would never apply for a job at an organization that does not support DEI.” A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of generation on whether employees would be unwilling to apply for a job at an organization that does not support diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F(3, 1246) = 16.06, p < .001. Bonferroni post hoc tests show that Gen Z (M = 2.20) and Millennials (M = 2.39) do not differ from one another (p = .08), but Gen Z has higher agreement than Gen X (M = 2.55, p < .001) and Baby Boomers (M = 2.79, p < .001). Millennials and Gen X do not differ (p = .13), but Millennials differ from Baby Boomers (p < .001). Gen X differs from Baby Boomers (p < .05).

- A chi square between intent to stay with employer long-term if they continue to support DEI and gender showed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,237) = 13.05, p < .001.

- A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of gender on whether employees would be unwilling to apply for a job at an organization that does not support diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F(1, 1235) = 34.68, p < .001. Women (M = 2.30) are more likely to agree than men (M = 2.63). Responses to “I would never apply for a job at an organization that does not support DEI” were dichotomized such that agree and strongly agree were coded as “1” and disagree and strongly disagree were coded as “0.”A chi square between never applying for a job at an organization that does not support DEI and gender showed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,237) = 16.53, p < .001.

- A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of gender on whether employees would be more likely to take a job with an organization that supports DEI. The results indicated a significant effect, F(1, 1235) = 27.06, p < .001. Women (M =1.96) are more likely to agree than men (M = 2.25). A chi square between likelihood of taking a job at an organization that supports DEI and gender showed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,237) = 18.29, p < .001.

- 1 in 3 companies that rolled back DEI initiatives are reinstating them. (2025). Resume Templates.

- Graham, K. (2024). Shaping success: A deep dive into women’s impact on the CPG landscape. Nielsen IQ.

- Pollard, A. (2021, November 17). Gen Z has $360 billion to spend, trick is getting them to buy. Bloomberg.

- Spend Z. (2025). World Data Lab.

- On a 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) Likert scale, employees were asked how much they agree with the statement, “I would be more likely to purchase a product or service from an organization that supports DEI.” A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of gender on whether employees are more likely to purchase products or services from companies that support diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F(1, 1235) = 31.82, p < .001. Women (M = 2.01) are more likely to purchase products or services from companies that support DEI, compared to men (M = 2.33). Responses to “I would be more likely to purchase a product or service from an organization that supports DEI” were dichotomized such that agree and strongly agree were coded as “1” and disagree and strongly disagree were coded as “0.”A chi square between likelihood to purchase from a company that supports DEI and gender showed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,237) = 17.64, p < .001. 74% of women are more likely to purchase from a company that supports DEI, compared to 63% of men.

- A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the impact of generation on whether employees are more likely to purchase products or services from companies that support diversity, equity, and inclusion. The results indicated a significant effect, F(3, 1246) = 18.44, p < .001. Bonferroni post hoc tests show that Gen Z (M = 1.90) and Millennials (M = 2.07) do not differ from one another (p = .16), and all other generations differ significantly from each other, with Gen X (M = 2.26) having the next highest level of agreement, followed by Baby Boomers (M = 2.52, ps < .05). A chi square between likelihood to purchase from a company that supports DEI and generation showed a significant association, χ² (3, n = 1,250) = 34.50, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that Gen Z (1.8) and Baby Boomers (-2.4) differed significantly from what was expected.

- On a 1 (positive correlation) to 5 (negative correlation) Likert scale, C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “In the past, have you seen a correlation between DEI programs and customer loyalty?” This question was dichotomized such that strong positive correlation and slight positive correlation were coded as “1” and no correlation, slight negative correlation, and strong negative were coded as “0.” A chi square analysis between prior correlation between DEI and customer loyalty and rank revealed no association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 2.23, p = .14. On a 1 (positive correlation) to 5 (negative correlation) Likert scale, C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “Over the next few years, how will continuing to support DEI programs correlate with customer loyalty?” This question was dichotomized such that strong positive correlation and slight positive correlation were coded as “1” and no correlation, slight negative correlation, and strong negative were coded as “0.” A chi square analysis between belief in a correlation between DEI and customer loyalty over the next few years and rank revealed no association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 3.42, p = .06

- On a 1 (positive correlation) to 5 (negative correlation) Likert scale, C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “In the past, have you seen a correlation between DEI programs and financial performance?” This question was dichotomized such that strong positive correlation and slight positive correlation were coded as “1” and no correlation, slight negative correlation, and strong negative were coded as “0.” A chi square analysis between prior correlation between DEI and financial performance and rank revealed no difference between C-suite and legal leaders, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = .37, p = .55.

- On a 1 (positive correlation) to 5 (negative correlation) Likert scale, C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “Over the next few years, how will continuing to support DEI programs correlate with financial performance?” This question was dichotomized such that strong positive correlation and slight positive correlation were coded as “1” and no correlation, slight negative correlation, and strong negative were coded as “0.” A chi square analysis between predicted future correlation between DEI and financial performance and rank revealed no association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 1.26, p = .26.

- On a 1 (very positive impact) to 5 (very negative impact) Likert scale, respondents were asked, “Right now, most executive and senior leader roles at U.S. organizations are held by White men. If organizations worked on diversifying these roles, how would that impact business outcomes such as innovation, creativity, and financial performance?” This question was dichotomized such that very positive impact and slight positive impact were coded as “1” and no effect, slight negative impact, and very negative impact were coded as “0.” A chi square analysis between belief that diversifying leadership will have a positive impact on business outcomes and rank revealed a significant association, χ² (2, n = 2,500) = 91.17, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that C-suite leaders (2.6) and Employees (-3.1) differed significantly from what was expected.

- C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “Has your organization taken any of the following steps to address the potential legal risks of your DEI programs, or will you do so in the near future?” Response options included: We are hiring additional DEI lawyers or consultants; we are assessing our DEI programs for legal compliance; we are creating a formal strategy/roadmap for the future of DEI at our organization; and we aren’t taking any steps

- C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “Within the past year, has your organization dealt with any of the following concerning its DEI programs?” Response options included: Social media attacks; threatening letters from advocacy groups; EEOC complaints or other charges/litigation; demonstrations or protests; and none of the above. A chi square analysis between experiencing social media attacks in the past year and federal contractor status revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 21.08, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that federal contractors (3.6) and non-federal contractor entities (-1.6) differed significantly from what was expected. A chi square analysis between receiving threatening letters from advocacy groups in the past year and federal contractor status revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 37.67, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that federal contractors (5.0) and non-federal contractor entities (-2.2) differed significantly from what was expected. A chi square analysis between experiencing EEOC complaints or other charges/litigation in the past year and federal contractor status revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 39.18, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that federal contractors (4.9) and non-federal contractor entities (-2.1) differed from what was expected. A chi square analysis between being the target of demonstrations or protests in the past year and federal contractor status revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,250) = 38.85, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that federal contractors (5.0) and non-federal contractor entities (-2.2) differed from what was expected.

- C-suite and legal leaders were asked, “Has your organization taken any of the following steps to address the potential legal risks of your DEI programs, or will you do so in the near future?” Response options included: We are hiring additional DEI lawyers or consultants; we are assessing our DEI programs for legal compliance;we are creating a formal strategy/roadmap for the future of DEI at our organization; and we aren’t taking any steps. A chi square analysis between the number of actions taken and federal vs non-federal contractor entities revealed a significant association, χ² (3, n = 1,250) = 53.16, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that federal contractors differed significantly at two (4.1) and three actions (-3.1) from what was expected.

- On a 1 (completely) to 4 (not at all) Likert scale, respondents were asked, “The values of diversity, equity, and inclusion can be incorporated into everyday workplace practices in many ways, including how meetings are conducted, how work is assigned, and how leaders and workers communicate with one another. To what extent is DEI incorporated into everyday workplace practices at your organization?” This question was dichotomized such that “completely” was coded as “1” and “somewhat,” “very little,” and “not at all” were coded as “0.” A chi square analysis between perception of embeddedness of DEI at one’s company and rank revealed a significant association, χ² (2, n = 2,500) = 117.51, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that C-suite leaders (4.3), legal leaders (3.0) and employees (-5.2) all differed significantly from what was expected.

- Respondents were asked, “Do you think your organization should rebrand or rename its DEI programs?” Response options included: 1 (Yes, my organization should completely rebrand); 2 (Yes, my organization should partially rebrand); or 3 (No, my organization should not rebrand its DEI programs). A chi square analysis between opinions on rebranding DEI at one’s company and rank revealed a significant association, χ² (2, n = 2,500) = 60.42, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that C-suite leaders (3.1), legal leaders (2.2) and employees (-3.8) all differed significantly from what was expected.

- As a follow-up to what extent is DEI incorporated into everyday workplace practices at your organization, respondents were asked, “How do you predict this might change over the next few years at your organization?” A chi square analysis between predicted change in embeddedness of DEI at one’s company and rank revealed a significant association, χ² (6, n = 2,500) = 182.53, p < .001. Examination of standardized residuals revealed that C-suite leaders (4.6), legal leaders (3.5) and employees (-5.6) all differed significantly from what was expected on endorsement of “DEI will become more incorporated into everyday practices.” C-suite leaders (-4.2), legal leaders (-3.4) and employees (5.3) also differed significantly from what was expected on endorsement of “DEI will become less incorporated into everyday practices.”